These evaluations serve not just as a diagnostic tool, but also as a means to ensure transparency and fairness in decisions that might impact one’s health, finances, or legal status.

However, a challenge that often emerges in this realm is the possibility of patients exaggerating or even fabricating their symptoms.

Whether these actions are motivated by external gains, such as financial benefits, or internal psychological needs, they pose significant implications for the integrity of medical assessments.

This article delves into the intricate world of malingering and factitious disorders, aiming to shed light on how IMEs play a crucial role in discerning genuine medical conditions from potentially deceptive presentations.

Definition and Distinction between Malingering and Factitious Disorders

Navigating the complexities of human behavior, especially within the confines of a medical setting, requires a nuanced understanding of the terms and concepts at play. At the forefront of this exploration are two conditions that are both perplexing and challenging to diagnose: malingering and factitious disorders.

- Malingering:

- Definition: Malingering is characterized by the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms. Unlike many other medical or psychological conditions, the driving force behind malingering is typically an external motivation. This could range from desiring to avoid work or military service, aiming to obtain financial benefits through fraudulent means, or seeking access to certain medications or other rewards.

- Factitious Disorders:

- Definition: Factitious disorders, on the other hand, are marked by the intentional feigning or production of physical or psychological symptoms. However, the distinguishing factor here is the absence of overt external rewards. Individuals with factitious disorders are driven by a need to assume the sick role, seeking attention, care, or sympathy, even in the absence of tangible benefits. It’s worth noting that this category also includes “Factitious Disorder Imposed on Another,” where an individual produces or fabricates symptoms in another person, typically a dependent.

- Differentiating Malingering and Factitious Disorders:

- While both conditions involve the deliberate portrayal of non-existent or exaggerated symptoms, the motivations behind each are distinct. Malingering is primarily driven by tangible external gains, whereas factitious disorders revolve around internal psychological needs. Recognizing this differentiation is crucial as the approach to assessment, intervention, and management varies based on the underlying motivations.

As the medical community continues to encounter these conditions, understanding their nuances becomes essential. Not only does it aid in the accurate diagnosis and appropriate management of affected individuals, but it also ensures that genuine medical concerns are not overshadowed by suspicions.

Importance of IMEs in Cases of Suspected Malingering or Factitious Disorders

The realm of medicine relies heavily on trust—a trust that patients accurately report their symptoms and histories and that doctors diagnose and treat them with utmost care and integrity. However, when the waters are muddied by conditions like malingering and factitious disorders, the system’s balance is disrupted. This is where Independent Medical Examinations (IMEs) step in as invaluable tools, ensuring fairness and authenticity in medical reporting.

- Societal Implications:

- Cases of undetected malingering or factitious disorders can have far-reaching societal implications. Beyond the immediate health risks posed to the individual, they can strain medical resources, leading to increased healthcare costs, wasted medical expertise on unnecessary investigations, and potentially depriving genuine patients of timely care.

- Medical Implications:

- For the medical profession, unidentified or improperly managed cases of malingering and factitious disorders can tarnish the reputation and trustworthiness of the healthcare system. Moreover, misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatments, which can have adverse effects on the patient’s health.

- Financial Implications:

- From a financial standpoint, undetected malingering, especially in legal or insurance contexts, can lead to fraudulent claims, resulting in significant economic losses. Insurers, employers, and other stakeholders have vested interests in ensuring that claims are genuine and justified.

- Role of IMEs in Addressing these Concerns:

- IMEs serve as an external, objective assessment tool in situations where malingering or factitious disorders are suspected. By bringing in a third-party medical professional to evaluate the case, it reduces the likelihood of biases or preconceived notions. Their primary goal is to provide an accurate representation of the patient’s medical condition, thus ensuring that any subsequent decisions—be it medical treatments, legal proceedings, or insurance claims—are based on factual and unbiased information.

The challenges presented by malingering and factitious disorders underscore the vital role of IMEs. In serving as a checkpoint for authenticity, they uphold the principles of transparency, integrity, and fairness in the complex interplay between medicine, law, and economics.

Guidelines and Procedures for Conducting IMEs in Such Cases

Conducting Independent Medical Examinations (IMEs) in the context of potential malingering or factitious disorders demands meticulousness and sensitivity. As these conditions involve deliberate falsification or exaggeration of symptoms, IMEs must be rigorous yet respectful, ensuring a comprehensive assessment without causing undue distress to the individual.

- Steps and Procedures during Examination:

- Patient History: Start with a detailed patient history, noting any discrepancies or inconsistencies in the narrative. This includes previous medical records, treatments, and responses to treatments.

- Physical Examinations: A thorough physical examination can sometimes reveal signs inconsistent with the reported symptoms. It’s essential to observe not just the presented symptoms but also the individual’s behavior and responses during the examination.

- Diagnostic Tests: Depending on the symptoms presented, relevant diagnostic tests, such as imaging or laboratory tests, may be ordered. The aim is to ascertain objective evidence supporting or refuting the claimed medical issues.

- Ethical Considerations:

- Respect and Sensitivity: It’s vital to approach individuals with respect, avoiding any confrontational or accusatory stance. A patient’s dignity should remain intact, irrespective of the examination’s outcome.

- Confidentiality: As with all medical evaluations, the findings of the IME should remain confidential, shared only with authorized parties.

- Informed Consent: Ensure that the individual understands the purpose of the IME and provides informed consent for the examination and any subsequent tests.

- Collaborative Approaches:

- Multidisciplinary Evaluations: Involving multiple specialists can offer a holistic view of the patient’s condition. For instance, a combination of medical doctors, psychologists, and other professionals might be ideal for a comprehensive assessment.

- Seeking Second Opinions: In complex or ambiguous cases, a second IME or consultation can be beneficial to confirm or challenge initial findings.

- Documentation and Reporting:

- Clear documentation of the examination process, findings, and conclusions is crucial. This not only aids in transparency but also provides a foundation for any further actions or decisions based on the IME.

Given the intricate nature of malingering and factitious disorders, IMEs pertaining to these conditions need to be both rigorous and empathetic. Balancing the quest for truth with the principles of medical ethics ensures that the process is just, thorough, and respectful of the individual’s rights and wellbeing.

Identifying and Assessing Individuals Presenting with Exaggerated or Fabricated Symptoms

As medical professionals navigate the complexities of malingering and factitious disorders, a key challenge is the identification and assessment of individuals who may be exaggerating or fabricating their symptoms. The line between genuine and feigned conditions can often be thin, but there are certain hallmarks that can guide clinicians in their evaluations.

- Common Red Flags and Patterns:

- Inconsistent Narratives: One of the primary indicators is the inconsistency in the individual’s account of their symptoms, medical history, or the onset and progression of their condition.

- Frequent Medical Consultations: Patients who often change doctors or frequently visit various medical facilities—often termed “doctor shopping”—might be seeking someone to validate their narrative.

- Symptoms that Defy Medical Logic: Presentation of symptoms that don’t align with known medical conditions or show an unusual progression can be suspect.

- Dramatic Descriptions: Overly dramatic or exaggerated descriptions of symptoms, especially when they don’t align with clinical findings, can be indicative.

- Behavioral Observations:

- Response to Testing: Patients might display abnormal responses to diagnostic procedures or tests. For instance, someone feigning unconsciousness might not respond appropriately to certain reflex tests.

- Awareness of Medical Terminology: A heightened familiarity with medical jargon, beyond what a typical patient might know, can sometimes be a flag, especially if used inappropriately.

- Behavior When Unobserved: Sometimes, individuals might behave differently when they believe they’re not being observed, which can offer clues about the genuineness of their condition.

- Psychological Evaluations:

- Engaging psychologists or psychiatrists can provide invaluable insights. Psychological testing can help assess an individual’s propensity to exaggerate or fabricate symptoms.

- The evaluations can also discern underlying psychological conditions that might be manifesting as physical symptoms, offering a different perspective on the presented symptoms.

- Role of Objective Findings:

- Relying solely on an individual’s account can be misleading. Objective evidence, whether from physical examinations or diagnostic tests, provides a more grounded foundation for assessment.

- Any discrepancies between reported symptoms and objective findings should be approached with caution, ensuring that genuine conditions aren’t overlooked in the process.

Tackling the enigma of malingering and factitious disorders requires a blend of clinical acumen, observation, and empathy. While it’s essential to safeguard the medical system from potential misuse, it’s equally critical to approach each individual with an open mind, ensuring that genuine medical conditions receive the attention and care they deserve.

Challenges and Limitations in IME for Malingering and Factitious Disorders

While Independent Medical Examinations (IMEs) stand as crucial tools in evaluating potential cases of malingering or factitious disorders, they are not without their challenges. The very nature of these conditions, rooted in deliberate concealment or exaggeration, presents numerous pitfalls that medical professionals must navigate with care and precision.

- Potential for Misdiagnosis:

- Overlooking Genuine Conditions: In the zeal to identify malingering or factitious behaviors, there’s a risk of overlooking genuine medical conditions. Dismissing real symptoms as feigned can have detrimental consequences for the patient’s health.

- False Accusations: Wrongly accusing someone of malingering or fabricating symptoms can lead to psychological distress, stigmatization, and potential legal repercussions.

- Limitations of Current Diagnostic Tools:

- Many diagnostic tools rely on objective evidence, which may not always provide clear answers in cases of malingering or factitious disorders.

- Psychological evaluations, though helpful, are not infallible. Personal biases, variations in assessment methods, and the patient’s ability to manipulate results can sometimes cloud findings.

- Patient Distress or Backlash:

- Raising suspicions or directly confronting individuals about potential exaggeration or fabrication can be distressing. This can damage the patient-doctor relationship, hinder future medical interactions, or lead to adversarial encounters.

- Patients who genuinely believe they’re suffering, even if their symptoms defy medical explanation, might feel invalidated or dismissed.

- Time and Resource Intensiveness:

- Comprehensive evaluations for suspected malingering or factitious disorders require considerable time, encompassing detailed patient histories, multiple tests, and possibly involving various specialists.

- Such exhaustive evaluations can strain medical resources, both in terms of manpower and costs.

- Legal and Ethical Implications:

- If an IME results in a legal or insurance claim being denied based on suspicions of malingering, the individual might pursue legal actions against the examiner or the involved institutions.

- Ensuring ethical considerations, such as the patient’s right to informed consent, confidentiality, and dignity, become paramount, especially in contentious cases.

Navigating the maze of malingering and factitious disorders through IMEs is a task fraught with challenges. It demands not only clinical expertise but also a deep sense of empathy, ethics, and a commitment to holistic patient care. Recognizing the limitations of the current evaluation methods and being aware of the potential pitfalls can guide professionals in offering a balanced, fair, and compassionate assessment.

Conclusion

In the intricate dance between medical truth and human behavior, Independent Medical Examinations (IMEs) for suspected malingering or factitious disorders occupy a crucial juncture. They serve as a testament to the medical profession’s dedication to authenticity, transparency, and the upholding of ethical principles. Yet, they also underscore the challenges of discerning genuine medical conditions from those potentially masked by ulterior motives.

As we’ve journeyed through the nuances of malingering and factitious disorders, one thing becomes evident: the importance of a comprehensive, compassionate, and ethically grounded approach to assessment. While IMEs provide a robust framework for objective evaluation, they must be balanced with empathy, ensuring that patients’ rights, dignity, and genuine health concerns are always at the forefront.

The intersection of behavioral patterns and medical diagnoses will continue to pose challenges. But with continued research, training, and a commitment to holistic patient care, the medical community can navigate these complexities, ensuring fairness, accuracy, and the overarching goal of patient well-being.

Historical Reference of Malingering

During World War II, malingering became a significant concern within the military. Soldiers sometimes feigned illness or injury to avoid combat duty. To address this issue, the military developed methods to detect malingering. The use of “malingering detection clinics” became widespread, where medical professionals were trained to identify soldiers who were exaggerating or fabricating symptoms to shirk their duties. These early efforts laid the groundwork for the understanding and recognition of malingering in a medical context.

Current Example of Factitious Disorders

In recent years, there has been growing concern about malingering in the context of disability claims, particularly related to mental health conditions. With an increasing number of individuals seeking disability benefits for conditions like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), some cases have raised suspicions of malingering.

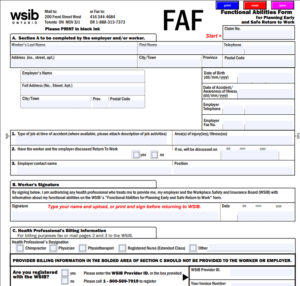

Insurance companies and government agencies responsible for disability assessments now employ specialized IMEs to assess the legitimacy of disability claims. These examinations involve detailed interviews, psychological evaluations, and the review of medical records. The goal is to distinguish between individuals genuinely in need of support and those who may be exaggerating or fabricating symptoms to secure financial benefits.

This underscores the ongoing relevance of malingering and the crucial role of IMEs in ensuring that resources are allocated fairly and that individuals with legitimate medical conditions receive the support they require.

Further Considerations

- The Historical Origins: The concept of malingering dates back to ancient Greece, where soldiers who pretended to be ill during wartime were called “skulkers.” This historical precedent demonstrates that the issue of feigned illness has long been a concern in human history, not just in modern medical and legal contexts.

- Role in Criminal Investigations: While IMEs are commonly associated with medical and legal settings, they also play a role in criminal investigations. Forensic psychologists may conduct IMEs to assess the mental state of individuals involved in criminal cases, helping determine their fitness to stand trial or their sanity at the time of the alleged crime.

- Factitious Disorder by Proxy: Factitious Disorder Imposed on Another (FDIA), a subtype of factitious disorders, involves individuals who intentionally cause illness or injury to someone under their care, often a child or dependent. This condition is sometimes referred to as “Munchausen syndrome by proxy” and has been the subject of high-profile criminal cases.

- Cultural Variations: The presentation and prevalence of malingering and factitious disorders can vary across different cultures. In some cultures, there may be unique motivations or manifestations of these behaviors, making it important for healthcare professionals to consider cultural factors in their assessments.

- Diagnostic Challenges: Malingering and factitious disorders can be extremely challenging to diagnose definitively. Some individuals are skilled at deceiving medical professionals, and the line between genuine and fabricated symptoms can be blurred. This complexity has led to ongoing research to develop more effective assessment tools and techniques.

FAQs About Malingering & Factitious Disorders

Are malingering and factitious disorders more common in certain demographic groups?

- Answer: There’s no clear evidence that these disorders are more prevalent in specific demographic groups. They can affect individuals of any age, gender, or background.

Can malingering or factitious disorders be successfully treated or managed?

- Answer: Treatment approaches vary depending on the underlying motivations and the individual’s willingness to engage in therapy. Factitious disorders may be linked to underlying psychological issues that can be addressed with therapy, while malingering typically requires addressing the external motivations behind the behavior.

Do individuals with factitious disorders ever genuinely believe they are sick?

- Answer: Yes, in some cases, individuals with factitious disorders may come to believe their fabricated symptoms over time, blurring the line between conscious deception and genuine belief in their illness.

Can malingering or factitious disorders coexist with genuine medical conditions?

- Answer: Yes, it is possible for individuals to have both a genuine medical condition and a malingering or factitious disorder. This makes diagnosis and treatment even more challenging, as healthcare providers need to address both aspects of the individual’s health.

Are there any medications that can specifically treat malingering or factitious disorders?

- Answer: There are no medications designed to treat these disorders directly. Treatment typically involves psychotherapy, counseling, and addressing underlying psychological issues if present.

How can healthcare professionals protect themselves from potential legal or ethical issues when assessing malingering or factitious disorders?

- Answer: Healthcare professionals must follow established ethical guidelines, maintain thorough documentation, and ensure that their assessments are based on objective evidence. They should also be aware of the legal regulations in their jurisdiction regarding reporting suspicions of fraud or deception.

Can malingering or factitious disorders be identified through brain imaging or other advanced technologies?

- Answer: While brain imaging and other technologies can provide valuable information, they are not typically used as standalone diagnostic tools for malingering or factitious disorders. These conditions are primarily assessed through clinical evaluation and observation.

Can individuals with factitious disorders recover and lead normal lives?

- Answer: Recovery is possible with appropriate treatment and support. Some individuals with factitious disorders may be able to lead fulfilling lives once the underlying issues are addressed through therapy and counseling.

Is it common for individuals with malingering or factitious disorders to seek multiple medical opinions?

- Answer: Yes, “doctor shopping” is a behavior often associated with malingering or factitious disorders. Individuals may seek multiple medical opinions in an attempt to validate their fabricated symptoms.

Are there any support groups or resources available for individuals with factitious disorders or those recovering from them?

- Answer: There are support groups and resources available for individuals with factitious disorders and their families. These can provide valuable guidance, understanding, and a sense of community for those affected by these challenging conditions.

Glossary of Terms Used in the Article

- Malingering: Deliberately exaggerating or feigning physical or psychological symptoms for external gains, such as financial benefits or avoiding responsibilities.

- Factitious Disorders: A group of psychological disorders characterized by the intentional feigning or production of physical or psychological symptoms without apparent external motivation.

- Independent Medical Examination (IME): A comprehensive medical evaluation conducted by a neutral, third-party medical professional to assess an individual’s medical condition, often in the context of litigation, insurance claims, or disability assessments.

- Skulkers: Historical term referring to soldiers in ancient Greece who pretended to be ill or injured to avoid combat duties.

- Doctor Shopping: The practice of seeking multiple medical opinions or visiting various healthcare providers in an attempt to validate fabricated symptoms or obtain specific treatments or medications.

- Psychological Testing: Assessment tools and techniques used by psychologists and psychiatrists to evaluate an individual’s mental health, cognitive functioning, and emotional well-being.

- Objective Evidence: Tangible, measurable, and observable data that supports or refutes the existence of a medical condition, as opposed to subjective reports or self-reported symptoms.

- Forensic Psychologist: A psychologist who applies psychological principles and assessments to legal and criminal justice contexts, including evaluating the mental state of individuals involved in legal cases.

- Factitious Disorder Imposed on Another (FDIA): A subtype of factitious disorders in which an individual intentionally produces or fabricates symptoms in another person, typically a dependent or family member.

- Informed Consent: The ethical principle that individuals must be fully informed about the purpose, risks, and procedures of any medical examination or treatment and provide their voluntary agreement to participate.

- Multidisciplinary Evaluation: An assessment approach that involves multiple specialists from various fields, such as medicine, psychology, and social work, to provide a comprehensive understanding of a patient’s condition.

- Diagnostic Tests: Medical examinations, including imaging and laboratory tests, used to obtain objective data that aids in diagnosing medical conditions.

- Confrontational Stance: An accusatory or hostile approach when addressing individuals suspected of malingering or factitious disorders, which can be counterproductive and harmful.

- Fitness to Stand Trial: An assessment of an individual’s mental and emotional state to determine whether they are mentally capable of participating in legal proceedings and understanding the charges against them.

- Holistic Patient Care: A healthcare approach that considers the physical, psychological, social, and emotional well-being of a patient, aiming for a comprehensive understanding and treatment of their condition.

- Stigmatization: The process of labeling, discriminating against, or marginalizing individuals with mental health conditions or those suspected of malingering or factitious disorders.

- Medicolegal: Relating to the intersection of medicine and law, often involving medical assessments or evaluations used in legal proceedings.

- Ethical Guidelines: Established principles and rules that healthcare professionals are expected to follow to ensure ethical conduct in their practice, including patient confidentiality, informed consent, and respect for dignity.

- Ulterior Motives: Hidden or underlying motivations that drive an individual’s actions, often not apparent on the surface but affecting their behavior and decisions.

- Genuine Health Concerns: Legitimate and bona fide medical conditions or illnesses that require appropriate medical attention and treatment, as opposed to fabricated or exaggerated symptoms.